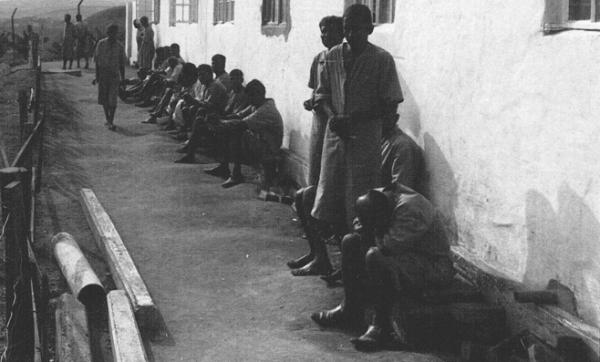

-- Fifty-one years ago, Citizens Commission on Human Rights discovered South Africa’s secret psychiatric slave labor camps, where 10,000 Blacks were incarcerated, largely for violating apartheid laws. In 1978, CCHR obtained a World Health Organization (WHO) investigation that condemned the camps. WHO substantiated that in addition to Black South Africans being used for slave labor, there was also a high death rate among the Black patients incarcerated in the for-profit private psychiatric institutions.[1] This month, CCHR International is monitoring a current inquest being held into the deaths of 144 patients between March and December 2016 who were transferred from the former apartheid hospital chain to unlicensed state community mental health centers.[2]

CCHR says monitoring is part of its ongoing watchdog role over abuses, especially patient deaths in psychiatric and behavioral hospitals. In recent years, CCHR has investigated and exposed the many deaths from restraint use, especially in for-profit psychiatric facilities in the U.S. and in other countries. In the U.S. there is a high number of African American teens dying from restraint use in for-profit behavioral hospitals. Recently, a former nurse of the now closed Lakeside behavioral hospital, pleaded no contest to a charge of third-degree child abuse in relation to the restraint death of African American teen, Cornelius Frederick in 2020.[3]

The health inquiry’s report, released in February 1996, was clear that: “Racism is still manifest in many aspects of psychiatric institutions” and “Culprits had committed gross abuses of patients with impunity.” This included frequent use of electroshock. In some hospitals “death certificates [were] falsified to camouflage the real cause of death.” The general treatment of patients, including involuntary commitment, isolation and drugging, had violated their “right not to be subjected to cruel, unusual and degrading forms of treatment,” Further, “The past policy of apartheid has been a source of malpractice and human rights violations.” Even after apartheid had ended, patients were being “treated as subhuman,” and children “made to bear conditions from which we protect the worst criminals in society.”[8]

It was also put on record: “As management of the institutions still remains largely in the hands of people who have previously implemented the policy of apartheid, this is still effectively maintained.” Moreover, “racial discrimination is still implemented in the most blatant manner as it is easy to do so with the patients who in the majority are not in a position to protest.”[9]

Many of the deaths were due to pneumonia and dehydration as the patients were hurriedly moved to 27 “poorly prepared” facilities in an apparent cost-cutting measure that showed evidence of neglect.[12] In 2018, police began investigating possible criminal charges against those involved.[13] Former deputy chief justice Dikgang Moseneke also ordered the government to pay financial compensation to 134 claimants who were affected by the tragedy.[14]

It has taken until August this year for an inquest to be held into those deaths and to also investigate accountability. Harriet Perlman, who developed an online Memorial and Advocacy Project for the victims said: “People want someone to be held accountable for what happened. One must not forget how cruelly people died and how hard it was to get compassionate and humane responses. People wouldn’t give answers; they lied and dismissed them.”[15]

CCHR says such actions are a significant reform compared to the cover up of the psychiatric abuses in the Smith Mitchell camps during apartheid. In 1976, the SA government passed a law making it a criminal offense to publish any exposure of the poor conditions in psychiatric institutions. Government officials had shares in some of the camps.

The TRC reported that the SPSA “did not play a proactive role in ensuring that the human rights of mentally ill people were upheld” during apartheid. Further, “the health profession as a whole was not outspoken enough in its protests against abuses.”[16] A UN report also stated the SPSA had resorted to “blatant falsehood in its defense of South African psychiatric care.”[17]

[1] CCHR’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC)Submission, May 1997, citing: American Journal of Psychiatry 136; 11, Nov. 1979, pp. 1501-1505

[2] “Life Esidimeni inquest kicks off on Monday, five years after deaths,” News 24, 5 July 2021, www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/life-esidimeni-inquest-kicks-off-on-monday-five-years-after-deaths-20210715

[3] “Nurse pleads to abuse in death at Kalamazoo youth home,” Wood 8 TV News, 29 Jul. 2021, www.woodtv.com/news/kalamazoo-county/nurse-pleads-to-abuse-in-death-at-kalamazoo-youth-home/

[4] Op. cit., CCHR’s TRC submission

[5] Ibid., citing: American Journal of Psychiatry. 136; 11, Nov. 1979, p. 1501

[6] “Apartheid and Health,” Part II, “The Health Implications of Racial Discrimination and Social Inequality: An Analytical Report to the Conference,” WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION (Geneva), 1983, p. 230

[7] www.researchgate.net/publication/278672387_Mental_Health_Care_in_South_Africa_1904_to_2004, p. 36; www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0037-80542018000300003&lng=en&tlng=en

[8] Report by Mental Health and Substance Abuse Committee, “Human Rights Violations and Alleged Malpractices in Psychiatric Institutions,” Nov. 1995, released Feb. 1996

[9] “Human Rights Violations and Alleged Malpractices in Psychiatric Institutions,” Report by the SA Mental Health and Substance Abuse Commit0074ee, Nov. 1995, released Feb. 1996.

[10] “Global mental health report blasts South Africa for Esidimeni,” News 24, 10 Oct. 2018, www.news24.com/health24/News/Public-Health/global-mental-health-report-blasts-south-africa-for-esidimeni-20181010; “Compensation for some Life Esidimeni families still outstanding,” Medical Brief, 17 Dec. 2018, www.medicalbrief.co.za/compensation-life-esidimeni-families-still-outstanding/

[11] Op. cit., News 24, 10 Oct. 2018

[12] “South African scandal after nearly 100 mental health patients die,” The Guardian, 1 Feb. 2017, www.theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/01/south-african-scandal-after-nearly-100-mental-health-patients-die

[13] Femi Oyedeji, “Criminal Justice System Has Let Us Down, Say Life Esidimeni Survivors’ Families,” News Direct, 19 Oct. 2020, newsdirect.co.za/2020/10/19/criminal-justice-system-has-let-us-down-say-life-esidimeni-survivors-families/

[14] Op. cit., Medical Brief, 17 Dec. 2018

[15] Op. cit., News 24, 5 July 2021

[16] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Vol. 4, 29 Oct. 1998, pp. 149-152, www.justice.gov.za/trc/report/finalreport/Volume%204.pdf

[17] “The Case for South Africa’s Expulsion from International Psychiatry,” United Nations Centre Against Apartheid report, May 1984, psimg.jstor.org/fsi/img/pdf/t0/10.5555/al.sff.document.nuun1984_04_final.pdf

Release ID: 89040897